An exciting interview with the President

Share

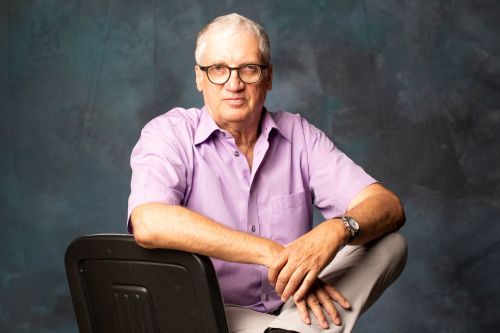

Franz Huber, Uri-based entrepreneur and founder of KoKoTé, shares his thoughts on what's important to him as an entrepreneur and how he came to establish an education and integration project for refugees. He also defines his concept of responsible entrepreneurship, of which the integration project and bag label KoKoTé is a successful example.

You've already run several companies, including the family business Hubrol AG, a heating oil supplier from central Switzerland, which you transformed into a more environmentally friendly company. However, you've also had to accept failures with other ideas and companies. What drives you to keep trying new things?

An entrepreneur simply does something (smiles). Sometimes it works out, sometimes not. With KoKoTé, I simply started without a concrete idea. I do write business plans, but they become outdated about every three months (laughs). It originally began with property conversions. I'm interested in how something can be developed further. 30 years ago, I decided that burning heating oil wasn't very smart. Since then, I've been studying how this could be further developed. That's been my drive and motivation. Especially when I was younger, I was attracted to ideas that seemed impossible. I was most motivated when someone said: that's impossible. That's why I had a few failures. It's possible that the wisdom of age catches up with you a little, but never completely (laughs).

In your opinion, what are the most important characteristics of an entrepreneur?

That it's not primarily about maximizing money, but about doing something meaningful. If you think an idea through and it's convincing, then it usually works. In the business world, there are many people who have ideas but no money, and people with money but no ideas. We have to find a middle ground there. That money isn't the only focus, but that it still plays a role. At KoKoTé, too, our goal is to be able to earn the money we need ourselves in three or four years so that we can write off our machines, so that we're up to date and can react to new developments. I also think it's important that entrepreneurs don't just say that their employees are the most important thing, but that they also live by it. So that theory and practice don't clash. If you keep these two or three maxims in mind, then a lot has already been achieved.

You're fully committed to responsible entrepreneurship. What exactly do you understand by this term?

Just making money doesn't appeal to me. Meaningfulness is very important to me, as is big-picture thinking. No outsider should pay the price for success. Be it nature, an employee or supplier being exploited, or customers being defrauded. It has to be a win-win situation for everyone. At Hubrol AG, we introduced employee participation systems for all levels 30 years ago. If the company does well and only the owner cashes in, I don't think that's responsible or honest. Whether it's a small company, Microsoft, or Amazon, it's not one genius who has brought these companies this far. It's a broad system that only works when people work well together. If one person is the boss, then that's more coincidence than intention. If you assume a craftsman: he's either a good craftsman or a good salesman, rarely both. If the salesman then rips off the craftsman, then that's not ethical in my opinion.

Inequalities have now been exacerbated by the pandemic, and the pandemic has also exposed weaknesses in the current economic system. In your view, should we move in this more responsible direction?

Absolutely. It's about ensuring that everyone who participates is visible, and that no one pays a hidden price or suffers for success. And that applies not only to me in Switzerland, but worldwide. If I work cleanly in Switzerland but can profit because I produce in a low-wage country where no occupational health and safety measures are observed, then that's not ethical for me. This also applies to us at KoKoTé. At KoKoTé, we only use recycled products. For us, the conscious choice of materials is not a marketing tool, but a matter of conviction.

How did you come to set up an education and integration project for refugees?

Let me back up a bit. When I was 19, I wanted to study psychology. But my father wanted me to join the company and do the commercial training, so that's what I did. Then, 30 years later, I trained as a systemic consultant and coach. Every training affects you. I came to the realization that living in Switzerland isn't a merit, but a matter of luck. And that I, in particular, was very lucky, on many levels. I wanted to build something for people who weren't as fortunate as I was. So, in 2015, it was a natural choice for me to work for refugees.

How did you come up with the idea of developing products in the bags/accessories sector, a highly competitive market?

My first thought wasn't: how can we earn money? I wanted to combine work and education, and to sew well, you don't need to be fluent in German. The refugees in Switzerland often have very good craft skills. Among other things, some can sew and already sewed in their homeland, in Afghanistan, Somalia, and Syria. It's a craft that almost doesn't exist here anymore. We wanted to utilize this resource, and that's how we started. And combining it with something you're good at makes it easier to learn something that's difficult—namely, German and finding your way around here. Little by little, a system of work and education emerged within the company, combining practical work with learning opportunities of varying intensity.

KoKoTé has come a long way in such a short time. What has surprised you the most, what did you not expect in the project's history so far?

Everything surprised me. I'm amazed at the number of social entrepreneurs who order company bags from us. They could order them much more cheaply from China. Many small and medium-sized companies, in particular, have managers whose social market economy is not only part of their mission statement, but is also implemented.

The project has existed since 2015. We launched under the KoKoTé brand at the end of 2019, and we achieved our budget targets in 2020, despite being massively impacted by the lockdown. I was very surprised by this. And this was split equally between B2C and B2B business. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, there's been a lot of talk about self-interest and egoism, but when I'm out and about—whether with business clients or private customers—I'm always amazed at how many socially committed people there are who not only appreciate quality but also value it.

What also always amazes me is that we don't sell the products I like best, but rather that customers usually prefer other products. Apparently, I don't have a good nose for that (laughs), and we develop our products together as a team with Carsten Joergensen.

What is your current vision for KoKoTé? Where do you see the brand in two or three years?

I have several visions. I want the KoKoTé brand to become an outward symbol of an inner attitude. And for the idea to be copied and spread. I'm 68 now, and in the next few years, I want to bring the business to a point where it becomes financially independent of me. Many of the dedicated people at KoKoTé work voluntarily; my wife Yvonne Herzog and I even pay for them (laughs). For me, economic success is part of it. I don't want to artificially keep an idea alive; it has to prove itself financially.

You founded the JLT Company and KoKoTé together with your wife, Yvonne Herzog. How does your collaboration work, and how does the separation of personal and business life work?

We don't separate our personal and professional lives. When I turned 50, we decided together that we would only do things we enjoy. That's not so easy. I get excited about an idea very quickly. The downside is that I sometimes end up involved in projects where I suddenly think: oh, I didn't want that at all. Now we're both over 60 and more goal-oriented; it works well. We complement each other. I've learned a lot from my wife, and perhaps she has learned a lot from me as well. We've continually developed through our collaboration.

In addition to your work as an entrepreneur, you also work as a coach. Who comes to you for consultations?

As a consultant, I'm becoming less and less active. I apply systemic knowledge to my work with refugees, clients, and partners. I still find it very exciting.

Looking back now, was your training as a systemic consultant a turning point for you? And something that significantly contributed to the success of KoKoTé?

Absolutely, I've changed a lot with this training. One of the most important parts of this training is the solution-focused approach. It starts with the attitude that there are no problems, there are only situations that you perceive as problematic, and the solution is part of the problem. This is an important insight that has helped me the most. You can apply it anywhere. It's most difficult when it comes to leading people. If someone says something stupid, you still have old patterns in you, and you tear your hair out.

I want to encourage the employee to find a solution themselves. Then it's sustainable. First, they won't be asking the same question every week, but rather they'll be taking a step toward development, and ultimately everyone will benefit. I find that very challenging, but also extremely exciting.

In your opinion, what would be needed for a more fundamental transformation to occur in the current economic system and for social values to become more important again?

Quite simply: I call it a democratization of the economy. Lisa Herzog, a German economist and philosopher who has written books on the subject, describes how in the Middle Ages, there were kings, princes, and the church that were untouchable. Now it's the large corporations, the great so-called leaders, who don't behave democratically, transparently, or respectfully. I recognize that you can't always vote on everything democratically. But you have to develop a system where everyone is involved in the decision-making process, wherever possible. A simple example: it would never occur to me to hire an employee without consulting those who will be working with them. If the team doesn't mesh, it won't work. If companies are run with pressure from the top, then you can't expect important information to trickle down from the bottom up. They only hear what the employees feel they want to hear. This way, they don't receive the relevant information. Sooner or later, this will have fatal consequences. In biology, it's defined as follows: closed systems die. This applies to us as well. This also applies to the climate issue. We are part of nature and live together with many other living beings. We are part of a whole, and if we don't open ourselves up and carefully consider what is interconnected and show consideration for one another, then we will die.

We are in the midst of very special and challenging times. What are your personal wishes for 2021?

I've decided to take things a little more slowly. I tend to get things done quickly, which has many advantages, but there are no advantages that don't also have disadvantages. Over 25 years ago, I tried to save the Tessag shoe factory, but I failed. That was very painful for me. And I also learned a lot in the process.

My intention and desire is to slow down, because often slower is faster. Slowing down is difficult for me; I'm often still very impatient. And by slowing down, I want to take care of my health, go for walks, and get plenty of exercise in nature.

Thank you, Franz, for this fascinating conversation!